Satellite analysis looked at credits sold by Finite Carbon, which runs some of North America’s largest offset projects

Some forest carbon offsets sold by the biggest offsetting company in the US offer little or no benefit to the climate, a satellite analysis has found.

Finite Carbon, created in 2009 and bought by British multinational oil and gas giant BP in 2020, is responsible for more than a quarter of the US’s total carbon credits, which it says it generates from protecting more than 60 “high credibility, high integrity projects” across 1.6m hectares (4m acres).

However, experts at the offsets ratings agency Renoster and the non-profit CarbonPlan analyzed three projects accounting for almost half of Finite Carbon’s total credits, with an estimated market value of $334m, according to analysis by market intelligence company AlliedOffsets. Renoster found issues, including trees in a project in the Alaska Panhandle that were probably never in danger of being cut down in an already extensively logged area. Of the credits Renoster looked at, they found that about 79% should not have been issued.

Renoster, a company mostly used by prospective buyers of carbon credits to help them avoid those without real climate benefits, was commissioned by the non-profit newsroom SourceMaterial to examine Finite’s projects. CarbonPlan provided additional analysis.

“We don’t think that the project should have been allowed to proceed and earn credits,” said Elias Ayrey, Renoster’s head scientist, commenting on the Alaskan project.

The analysis comes amid mounting concern about the global offsetting industry, predicted by Barclays bank to be worth $1.5tn by 2050. The US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, in May unveiled new principles to help strengthen the carbon market in an effort to “address significant existing challenges”, saying she had seen too many examples of offsets which didn’t represent real emissions reductions.

Critics say the industry has fundamental failings, and some companies have been shifting away from offsets. Last year the Guardian, SourceMaterial and the German newspaper Die Zeit revealed that as many as 90% of the most commonly traded offsets may be practically useless in mitigating global warming.

Finite runs some of the largest offsetting projects in North America. Under California’s cap-and-trade system, it earns credits from across the US which it sells to polluters to offset their emissions.

In theory, developers like Finite encourage landowners to protect trees that would otherwise be cut down so that they continue to absorb carbon from the atmosphere. Finite says its projects have nullified more than 70m tonnes of harmful emissions, the equivalent of 18 coal plants running for a year – and more than double the total emissions BP reported last year.

Critics, though, say California’s flawed offsetting system is handing companies a license to pollute with impunity. “The potential for mischief, for gaming … is just overwhelming,” said Mark Trexler, an independent climate scientist who created the first offsetting project in 1989.

Asked about Renoster’s analysis, Finite Carbon did not respond to specific questions but defended its offsets.

“All Finite Carbon’s compliance market projects have been independently verified, developed in accordance with the applicable standards and protocols under the California cap-and-trade program, and the projects have all been approved by the California air resources board,” said Brendan Terry, a Finite Carbon spokesperson.

BP directed requests to comment to Finite Carbon. The multinational oil and gas company praised Finite Carbon during its acquisition.

Potential for ‘gaming’ the system

The way the offsets work is that to justify claims that forests are being saved, each project is based on a “baseline,” which is a calculation of how many trees would be lost if the program did not exist.

Finite’s Sealaska project in the Alaskan Panhandle says it is protecting 67,000 hectares of forest. The project is owned by the Sealaska corporation, a for-profit company created in 1972 and owned by Alaska Natives. The credits this project has generated are valued at over $100m, according to analysis by Allied Offsets.

Using satellite imagery, Renoster found that trees there face little to no risk of ever being cut down. That’s because the corporation has already logged the vast majority of the land around the project. The only trees still standing are in deep ravines, along roadsides, rivers and coastlines. Instead of including the deforested land, Finite drew circles around thousands of tiny areas where trees were still standing, creating a hugely complicated map. In one of the project’s areas, Finite had circled fewer than 50 trees on a tiny island off the coast.

Renoster’s satellite analysis concluded: “They are not at risk of deforestation and thus should not be receiving credits.”

While this approach may be within the rules in California, where the credits are sold, it undermines the spirit of the regulations, Renoster concluded. Renoster gave the project a score of zero, meaning it thinks it should not be issued any credits.

Although some conservation may be going on, the “gerrymandering” made it impossible to assess, Ayrey said. “We have a zero tolerance policy on this behavior,” he said.

The report concluded: “We consider this type of manipulation to be ‘cheating’ … The drawing of these boundaries is an intentional act designed to avoid protocol rules.”

Asked about the findings, Sealasaka representatives said the trees left behind did hold economic value and were legal to cut down, but they opted not to because of Finite’s program. The former Sealaska executive vice-president Rick Harris said at one point prices for chartering helicopters dropped to such low levels that the company could afford to hire them to cut down low-value pulp logs.

Brian Kleinhenz, who helped develop the credits while working at Sealaska and is now president of the carbon offsetting developer Terra Verde, said there was always value in the trees, even if they are hard to get at. “There’s going to be a market for all this material, in one way or another,” he said.

Dave Clegern, public information officer for the California Air Resources Board (Carb), said: “If trees on steep terrain are valuable enough to warrant the cost of getting there and moving logs down the mountaintop, then they may be included in a baseline calculation.

“These rules would apply with Sealaska,” he said.

Ayrey, however, argued the evidence did not support this.

“The strongest piece of evidence is the obvious,” he said. “They’ve clearcut vast tracts around these trees and left them in place. Most of these clearcuts date to [more than] 20 years ago and if it were profitable to access these sites, they would have done it then.”

Alleged over-crediting

Another Finite project analyzed by Renoster for SourceMaterial in West Virginia scored above zero, meaning it should be awarded some credits. But it was “over-credited”, the findings showed.

The 39,000-hectare project is owned by Lyme Timber Company, which promised to preserve some trees in exchange for carbon credits. Renoster found that many of these trees were “inaccessible due to steep slopes”, meaning Lyme couldn’t actually cut them down.

David P Hoffer, president of Lyme Timber, said the project had already been developed when his company purchased the land.

“With respect to harvesting activity, contrary to the Renoster report, Lyme has harvested substantially less than biological growth since we purchased the property in 2017,” he said.

Carb’s Clegern said concerns had been raised about Lyme’s program but were ultimately cleared by the state of West Virginia and a registered forester.

“The verifiers are reasonably assured that despite the highly variable terrain and steep slopes found on the project area, they would allow for traditional harvesting techniques,” he said.

Clegern added: “To the best of our knowledge, the project is in conformance with all regulatory and protocol requirements.”

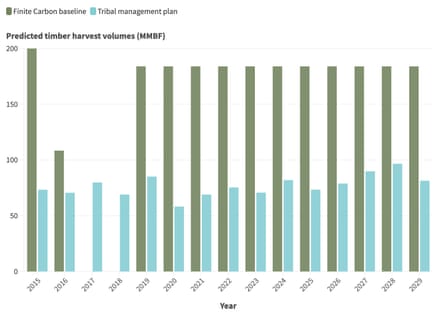

Another project is a 200,000-hectare (494,000-acre) forest in Washington state owned by the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Finite’s offsetting calculations imagined a risk of far more logging than the tribes had planned – or had ever done before – according to Grayson Badgley, a scientist at CarbonPlan.

“One of the last things you want to do with offsets is pay someone not to do something they were never planning to do anyway,” Badgley said. “A significant number of credits may have been awarded for forgoing harvests that were unlikely to ever happen.”

Representatives for Colville did not respond to requests for comment. Clergen said Carb had not received any complaints about Colville’s carbon project.

California dreaming

Experts question whether California’s cap-and-trade system, through which Finite sells most of its credits, is a solution to climate change – or part of the problem.

Sellers have an interest in maximizing the volume of credits, while buyers have no incentive to question their effectiveness, said Trexler, the climate scientist.

“Everyone involved in designing these projects and protocols has an interest in generating credits,” he said. “Mother Nature … is not at the table when these rules are designed.”

California’s forest project methodology was designed with assistance from the carbon offsets industry. Finite’s co-founder, Sean Carney, took part in meetings to draft the Carb standards in 2008, just months before he set up the company, minutes show.

Yet despite the criticism, Carb, which since 2013 has required companies exceeding emissions limits to buy offsets, said it was not planning any changes to address the risk of over-crediting, according to Danny Cullenward, vice-chair of California’s Independent Emissions Market Advisory, the official oversight committee for the cap-and-trade system.

“Carb is hostile to everybody who’s critical, and they’re friendly with all the lobbyists,” Cullenward said. “That’s the way things are done.”

Responded Clegern: “Carb’s offset program has been successfully litigated in court and found to deliver real, quantifiable and additional benefits.”

‘Too good to be true’

The expansion of Finite’s projects has had setbacks.

In 2012, a representative from the company approached the Hoopa Valley tribe, owners of a 36,180-hectare forest in northern California.

The company had an incredible proposition: if the tribe simply continued to manage its ancestral lands as it had always done, Finite would generate carbon credits worth millions. The tribe would be rich.

“They were saying: ‘You guys manage your forest so well that what you’re doing now would earn you carbon credits, and you wouldn’t have to do anything new,’” said Julia Hostler, a member of the tribe. “It sounded too good to be true.”

Finite Carbon said it was company policy not to comment on projects that are not finalized, including on the Hoopa Reservation.

Tribal leaders ultimately did not pursue the company’s proposal.

They became uneasy after suggestions that they “rewrite and resubmit the forest management plan to allow theoretically greater harvest, in order to show we have discretion to harvest, or choose not to harvest, and thus get carbon credits”, according to emails provided by a tribal member.

The tribe now has “a strong wall against carbon brokers”, said Thomas Joseph, a tribe member and environmental educator.

For the Hoopa it’s personal, he explains. Recent years have seen tribal lands ravaged by wildfires made more extreme by climate change, and there is a realization that carbon markets have played a role in allowing companies to pollute.

“For us to be able to protect our lands, we need a reduction of emissions,” he said. “Not only would we be putting our community here in danger, and sacrificing our lands to corporate greed, we’d also be allowing the industry to not reduce its emissions.”