LA CONCHITA, Calif. — In the surfer’s paradise where Mike Bell has lived for four decades, talking about rain is blasphemy. “We have sprinkles, we have showers, we have mist, but we don’t use the ‘r’ word, because the ‘r’ word is what kills people,” he says.

Fifteen years ago, after 18 inches of it fell in just over two weeks, terrain that slopes through his small, tightknit town morphed into a massive mud avalanche and buried several dozen houses. Ten people died, including three young sisters.

Almost exactly 13 years later, just a short drive up the coast in Montecito, another post-rain mudslide washed away more than 100 homes. Witnesses said it sounded like a freight train crashing through. Twenty-three people were buried.

On the anniversaries of the disasters — one on Jan. 10, 2005, and the other on Jan. 9, 2018 — the two seaside communities are still grappling with hard decisions stemming from the destruction and loss of life. Yet they’ve made very different progress along their paths to recovery.

Affluent Montecito is anticipating county and federal funds to move forward with plans to build a basin to contain deadly debris the next time the ground turns liquid. In working-class La Conchita, however, support for a proposed hill-grading project has come and gone, followed by acrimony and anger.

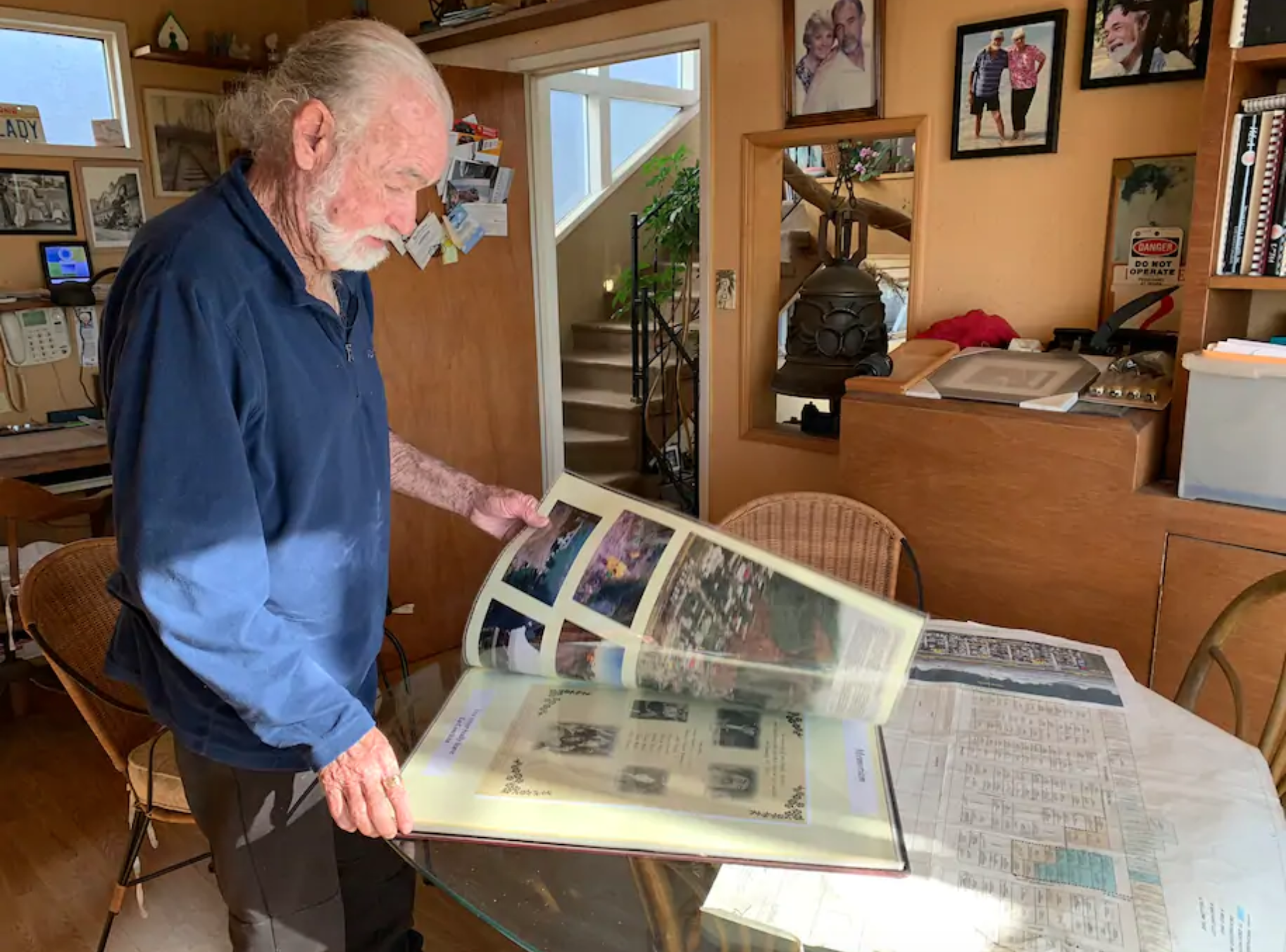

Residents can only hope they will be far enough away from the next flow. “Everybody says a prayer at night,” according to Bell, who at 72 is regarded as the unofficial mayor.

The challenges both places face raise questions that scientists say are increasingly likely to confront other California cities and towns, especially given the threats from climate change: If a future natural disaster is probable, at what cost can a community be protected? And if residents can’t afford that, where do they go?

Santa Barbara and Ventura counties are as vulnerable as any; geologists who study southern California’s terrain say future slides and flows there are both natural and inevitable, part of a drought-to-deluge cycle.

In the immediate wake of La Conchita’s tragedy, involving an estimated 400,000 tons of earth, then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger visited and promised to make the Ventura County community safe. He said he’d be back. He never was — and the money needed to fulfill his promise never came.

Scientist Randall Jibson of the U.S. Geological Survey was at the scene days after the event. He heard residents describe La Conchita as idyllic, tucked tightly between mountains and ocean. “I heard the term heaven,” he recalled recently. “Yet from time to time, it turns into hell instead.”

In his 2005 report on future danger, he concluded that the community was likely to experience “a rather bewildering variety of landslide hazards.” A later study commissioned by the state found that protecting La Conchita would require building steps into the 500-foot hill directly behind it. The cost was estimated as high as $50 million. The median income in La Conchita and the surrounding area is $54,565, according to census records.

“The problem is, everybody knows what would need to be done to stabilize the hillside and everybody wants everyone else to pay for it,” Jibson said. “The community can’t afford it, the county can’t afford it, and the state doesn’t feel like it’s responsible for it.”

Ventura Supervisor Steve Bennett, who has represented La Conchita’s part of the county for 19 years, said officials were never going to foot the multimillion-dollar project: “Basically, it’s an enormous amount of money . . . It’s not something that I’m willing to commit the taxpayers to do.”

The county did pay to remove rubble from adjacent streets and yards and put up signs saying the area was geologically unsafe to inhabit or visit. Bennett said he asked the Federal Emergency Management Agency to consider buying out residents and creating a park, but the idea was rejected.

In his view, those who remain do so at their own risk.

The conversations have been much different in neighboring Santa Barbara. A remedy for Montecito — where celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey live and homes sell for millions — has never been a question of money or support.

The speed and scale of devastation seen there were stunning. It followed a late-night cloudburst that in 15 minutes dumped nearly an inch of rain on bone-dry hills recently scorched by the historic Thomas Fire.

Curtis Skene, 66, awoke to the sound of wood cracking everywhere. A moment later, his bedroom wall ripped open “and eight to 10 feet of mud and debris just rushed into the room.” He barely escaped.

The private-equity specialist, who grew up in Montecito, vowed to lead an effort to prevent future slides even if it meant residents had to raise some of the funding. At a subsequent community meeting, he struck up a friendship with the county’s deputy director of water resources. Together they devised a plan to build a new flood basin on one of the streets that had been wiped out. Its projected cost: upward of $25 million.

Tom Fayram “looked me in the eye and said, ‘I’m willing to work with you on this. I’m willing to put my reputation on the line to help make this happen,’ ” Skene said.

Skene went door to door to drum up support. He convinced the handful of property owners whose empty lots would be used for the project to sell to the county, which agreed to pick up a quarter of the bill and to work with FEMA to pay for the remainder. Although the agency hasn’t officially signed off on the plan, Skene and Fayram say officials at a meeting in Sacramento last August told them the plan had been approved and was just awaiting final environmental review.

At that point, Santa Barbara had already bought the first of eight properties needed for the basin. Its seller, for $4 million, was the president of Johns Hopkins University and his wife. The project’s expected groundbreaking is summer 2021.

La Conchita is still waiting for some significant safety or mitigation effort. Untamed dirt from the 2005 slide still comes up to the back of several second-story homes, and a street that once encircled the town is now permanently closed since portions were never rebuilt. The local emergency plan includes a shed paid for by residents and filled with a tractor, generator, floodlights and folding chairs.

“The county never will ever do something unless we have another slide,” Bell said. “And if it does, it likely will fall where it fell. And if it does that, hopefully nobody gets killed.”

No matter the risk, he intends to stay put to the end. “This is the greatest place in the world to live,” he said, looking out a bedroom window to panoramic views of the ocean. “I’ll go out of here with a toe tag.”