Trump fought Californian environmental officials. The Biden team wants to learn from them.

No state has weathered the brunt of the Trump administration’s climate skepticism like California. During the past four years, the president stripped the Golden State of its ability to regulate car emissions, threatened to withhold emergency wildfire funds due to supposed forest mismanagement, and rolled back environmental protections the state—home to the nation’s worst air quality—desperately needs.

Yet after years in the trenches fighting the executive through both tweets and lawsuits, California is on the precipice of a major power shift. The Biden team wants Californian expertise.

“The truth is, they want to know everything. I’m getting dizzy,” said Jared Blumenfeld, California’s secretary for environmental protection, about the frequent meetings and webinars his agency has been having with the Biden transition team. “They’re genuinely interested because we’ve been going it alone in some regards.… We kept the torch alive during some pretty dark years for the environment.”

While the Trump administration doggedly repealed and weakened more than 125 national environmental rules, erasing mention of climate change on websites and memos, California stayed the course, committing to the emissions-cutting targets of the Paris climate accord. To meet those targets, the state peered into every one of its industries to find ways to cut greenhouse gases.

California’s pathbreaking climate measures range from a ban on future car combustion engine sales to setting a historic 100 percent clean energy goal by 2045. And in order to implement Joe Biden’s still more ambitious campaign promise to run the country entirely on carbon-free energy by 2035, the transition is looking to pull from what’s worked out West, teeing up a relationship that will give the Golden State an influential role in helping shape federal climate policy.

“California has sort of been the vanguard here on some of the specific policies,” said Sam Ricketts, former climate director for Washington Governor Jay Inslee’s presidential campaign. “There is much that the Biden administration can learn from in terms of California leadership, and there’s much the California leadership is going to continue to do to drive the policy debate forward federally.”

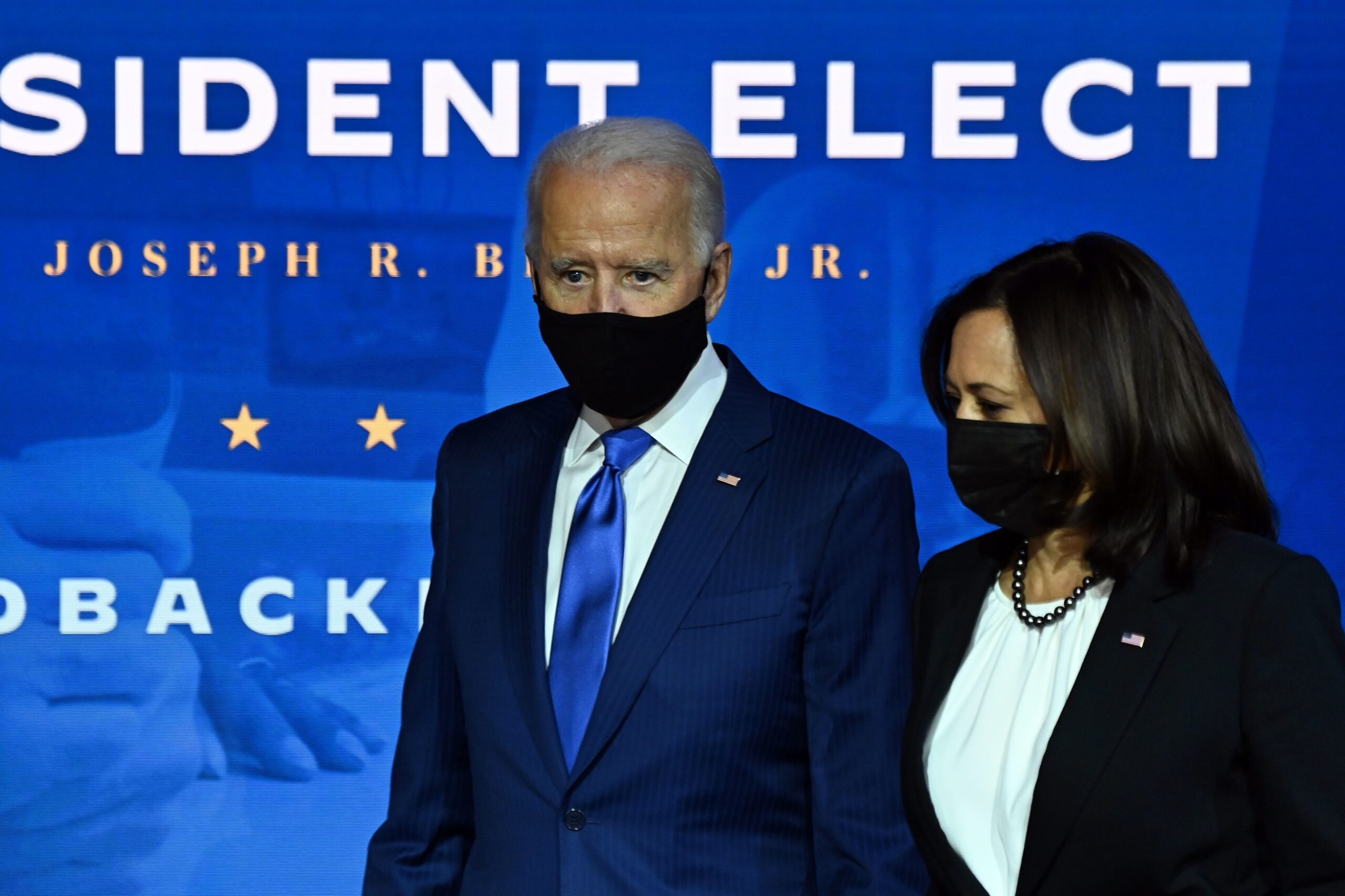

The Biden team is already thinking of poaching some of the state’s officials. California Air and Resources Board Chair Mary Nichols, a stalwart of the state’s climate policy efforts, is reportedly being considered to lead the Environmental Protection Agency under Biden after she retires this year. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, who has pushed ambitious emissions-reduction goals in the city, is being considered for transportation secretary. And California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, who aggressively pursued more than 100 lawsuits against the Trump administration, many of which challenged environmental deregulations, was officially chosen this week to be Biden’s secretary of health and human services. Then, of course, there is Vice President–elect Kamala Harris, formerly a California senator and attorney general. The personnel choices are expected to strengthen and rebuild a Washington–West Coast relationship that suffered during the Trump years.

Blumenfeld knows Harris personally from her attorney general days, when he led the EPA’s Region 9 office in San Francisco. “The vice president–elect is a very strong environmentalist … she understands that intersectionality of racism and environmental protection and equity, and I think having knowledge of California in D.C. is incredibly valuable,” said Blumenfeld, who added he expects Harris to be a “translator” for the White House. “We hope we can share the things that we’ve learned to make the administration as successful as it possibly can be.”

The federal government isn’t the only one that would benefit from a closer D.C.-California relationship. While California has frequently led on environmental issues, setting regulations with national reverberations due to the state’s position as the fifth-largest global economy, last year the Trump administration severely curtailed that. The Trump EPA’s move to revoke California’s waiver under the Clean Air Act and fully rewrite the fuel efficiency rule this March set the state back immensely when it came to hitting its climate targets. Without the waiver in place—which allowed California to set more stringent regulations for car tailpipe emissions—one estimate finds that the state will miss its 2030 target.

There’s only so much a state can do without federal leadership. Nichols attempted to forge state tailpipe emissions agreements with car manufacturers but was met with lawsuits. But since the election results, moods have shifted. General Motors in late November announced it was dropping its joint suit with the Trump administration, writing: “We are confident that the Biden Administration, California, and the U.S. auto industry, which supports 10.3 million jobs, can collaboratively find the pathway that will deliver an all-electric future.” On Friday, Nissan also withdrew its support for the lawsuit.

The Biden administration needs California because timing is tight: both the timeline set by the Biden climate plan and the one set by United Nations scientists, who estimated that the globe could hit a massively disruptive 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming above preindustrial levels as early as 2030.

“One of the things that California has been so important for is really experimenting and demonstrating what works … so there’s a lot of opportunity for learning from those experiences,” said Ann Carlson, a professor of environmental law at UCLA. “That’s sort of the hallmark of federalism. States are laboratories, and no state has been a bigger laboratory for climate policy than California.”

Biden’s climate plan already pulls strongly from many Californian initiatives, including the push for 100 percent clean emissions vehicles and energy efficiency in buildings. “The use of performance standards to transform individual sectors of the economy has been crucially important,” said Ricketts, who has been in conversations with Biden’s team and has suggested climate policies to adopt. “California notably had the first carbon market. Then there’s the state renewable portfolio standard, and now the state’s 100 percent clean electricity standard is arriving for renewables in the electricity grid.”

The federal government is also likely to pull from the state’s detailed method of mapping environmental impacts across disenfranchised communities to build an intersectional understanding of environmental justice. The Biden team has committed 40 percent of funding under his nearly $2 trillion plan to disenfranchised communities.

But it remains to be seen how adept the Biden administration is at scaling and rolling out its initiatives. “One of the really frustrating things about federal policy is that we need fast emission reductions, and we need them to be really deep. Had we started 20 years ago, we’d be in a lot better shape,” said Carlson. “I think the hard challenge is going to be, how to deeply cut emissions over a very short timeframe, in a way that is distributed and totally fair, that … protects the most disadvantaged communit[ies] and provides them with real access to clean energy.”

Experts also agree California isn’t perfect: It, too, has a ways to go when it comes to, for example, recycling infrastructure, clean energy job growth, and environmental justice remediation.

Blumenfeld anticipates the state’s relationship with Biden may also not always be rosy. “There’s a sense that it’s just going to be a complete lovefest, and we hope that it is,” he said. “But California will keep pushing. So our role as an agitator is gonna continue … this fight is really the fight of our lifetimes,” he said, comparing potential disagreements with the Biden team to being “angry with your friends.”

Not everyone will be happy with the idea of California taking a prominent lead in shaping federal climate policy—especially conservatives. Policy experts, however, argue that California’s climate policies should be seen through apolitical, empirical success metrics.

“The foundational climate policies in California were passed under Republican Governor [Arnold] Schwarzenegger. The thing to drive home to people who might see … the California model as a sort of left-coast imposition, is actually that what underpins California’s approach has been bipartisanship, pragmatism, science-based targets, and very talented civil servants,” said Aimee Barnes, senior adviser to former California Governor Jerry Brown. “I think that those broad categories are a winning combination, regardless of where you are in the country.”

Blumenfeld said he hopes the discussion around climate action can simply boil down to choosing the best ideas. “We’ve had so much devastation and trauma and death in the last four years because of turning a blind eye to science and public health that my hope is that we can get to a place where the best idea is the one that wins,” he said. California “should only be listened to if we have good ideas that make sense, that help us grow as a country. And I think the truth is that we do.”