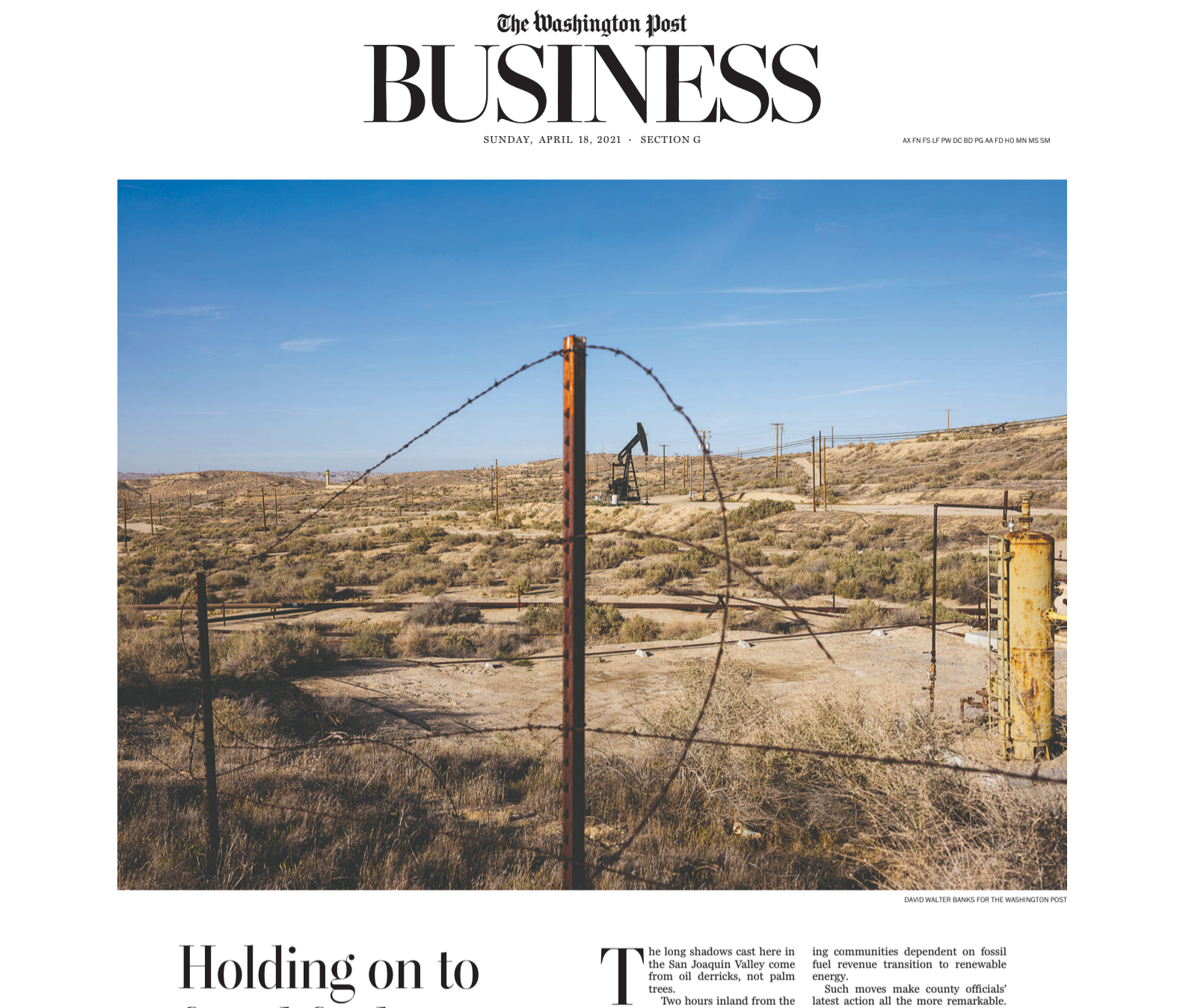

WASCO, Calif. — The long shadows cast here in the San Joaquin Valley come from oil derricks, not palm trees.

Two hours inland from the Pacific Ocean, the arid terrain is peppered with petroleum and gas wells. The black gold that lies underground became the region’s lifeblood after it was discovered in 1899, and Kern County is still responsible for more than 70 percent of oil and 80 percent of natural gas produced in California.

“We are very proud of our oil industry and our contribution to national security,” said Dave Noerr, the mayor of Taft, a city of 9,400 in the southwest foothills. “We’re just a bunch of hard-working, America-loving, good ol’ boys.”

Yet in a distinctly blue state that has pledged to slash greenhouse gas emissions within a decade, drilling seems on borrowed time even in this red county. Locals are watching legislators in Sacramento push bills to meet California’s climate goals, while in Washington the Biden administration’s focus is on helping communities dependent on fossil fuel revenue transition to renewable energy.

Such moves make county officials’ latest action all the more remarkable. The Board of Supervisors unanimously approved an ordinance in March that’s likely to significantly accelerate drilling — with as many as 40,000 new oil and gas wells in Kern by mid-2030. Its language, crafted in consultation with the industry, includes a blanket environmental impact statement that will make it easier for companies to get drilling permits.

“We all realize change is inevitable. New technology, new innovations will eventually change the way we produce and consume energy in the future,” Chairman Phillip Peters, whose family has deep roots in oil, said just before the vote. “But while we are looking at that, I don’t think we can ignore the present. The world still runs on Kern oil.”

The outcome, following a nine-hour hearing that was one of the longest in board history, is a window on the stakes involved as communities and states try to shift away from fossil fuels to slow climate change.

In Kern, it raises land-use and groundwater issues, further pitting the oil and gas industry against the equally important agricultural sector. For the region’s large Hispanic community — families who live or work near the open wells — it puts their health even more in the crosshairs.

“The reality is that we’re so afraid,” Estela Escoto said Tuesday through an interpreter. “Everything that the oil industry and the gas industry have dumped into our communities are only bad things.”

On a hot afternoon, residents can barely see the Sierra Nevada mountains that border the valley to the east because of the dense pollution. Drilled wells release greenhouse gas emissions that are major contributors to climate change and respiratory problems. The closer the proximity to the source, studies show, the higher the risk.

In 2020, Kern was ranked the worst U.S. county for year-round particle pollution in the American Lung Association’s annual report. A high proportion of Kern’s “disadvantaged community” lives near emissions sources such as extraction, distribution and refining sites, according to state data.

When Escoto and her husband moved from Los Angeles to the small city of Arvin, which sits southeast of Bakersfield, it was to buy their “dream” retirement home. But it didn’t take long before both were dealing with extreme year-round allergies. Escoto’s throat would get so itchy that she dreamed of shoving her hand down it to scratch.

“We went to the doctor and he told us, ‘You live in Arvin? Well then, I recommend that you move, because it’s one of the most polluted communities,’” Escoto recalled. “At first, we laughed. Then we got mad.”

She now heads the Committee for a Better Arvin, a local environmental justice group that was among the plaintiffs in a lawsuit fighting the original environmental impact assessment needed for proposed wells. The outcome forced the county to require greater pollution mitigation by companies. Some of the same plaintiffs are now challenging the supervisors’ latest vote, which they believe was motivated by the tax dollars and jobs that new wells represent.

“We feel neglected. We feel that they are not taking us seriously,” Escoto said of the board, which she says ignored a request to provide meeting materials about the ordinance in Spanish. “And they decided to come and put an ordinance that would allow thousands of oil wells in a span of 15 years. … It completely sets aside our suffering, our struggles.”

The fossil fuel industry has strong ties to Kern. Towns bear the names “Oildale” and “Oil City.” The American Petroleum Institute adopts its highways. A program that lets local high school students take math, science or engineering classes free at California State University Bakersfield is funded by and named after Chevron. The oil and gas industry also pays upward of $197 million in yearly property taxes, money that helps pay for teachers, police officers and firefighters. That isn’t lost on residents.

“People don’t fully understand, not just the contributions that come from oil and gas, but the need for it,” Noerr said, “especially in the state of California.”

The county has more than 47,000 active wells and more than 25,000 idle wells, according to data from the California Geologic Energy Management Division. They’re readily visible from roadways. Many are only hundreds of feet from homes, schools and farms.

Farmers worry about what’s to come and how their land — which produces a bounty of almonds, grapes and pistachios — will be affected in the long term. They note their importance to the county, with agriculture a vital economic force in Kern. Nearly 6 percent of jobs are in the extraction or construction industries, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Farming, fishing and forestry jobs constitute 13 percent.

“My immediate concern is how they treat our surface, how much acreage they take out of farming,” said almond farmer Keith Gardiner, who owns and operates more than 20,000 acres in addition to a farm management company in Kern. He contends that he has “lost millions” in revenue because of groundwater contamination over the years.

The area’s oil and farm industries have always run parallel to one another, but tensions have been escalating. Kern County is one of the few parts of California to allow hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in which water, sand and chemicals are injected into the bedrock under high pressure to facilitate the extraction of petroleum or natural gas.

“Early on, there wasn’t much drilling in our prime farmland areas. It was always on the fringes,” Gardiner recalled. “But as those reserves were tapped and as fracking became really widespread, they figured out how to frack this shale … Then there started to be more controversy.”

He and other farmers fear more wells will mean a higher likelihood of salinated water leaching into clean groundwater. There’s also concern that uncapped idle or orphaned wells, for which no one takes legal or financial responsibility, will only increase in number. Methane emissions from such sites are significant nationally.

State regulations may soon shift the dynamics and place new pressures on local leaders. A comprehensive bill that would ban fracking statewide and halt other oil-extraction techniques is making its way through the legislature. If passed, it would stop wells from operating within 2,500 feet of schools and homes, a provision heralded by environmental groups and denounced by oil and gas officials.

“We would be out of business,” said Rock Zierman, chief executive of the California Independent Petroleum Association. The bill would “completely shut down our entire industry.”

Kern’s supervisors think the legislative measure is out of touch with reality, given California’s continued reliance on fossil fuels. They know their county has a lot at stake.

“We have the jobs. We have the tax revenue. The amount of money that goes into our local economy, it’s incredible,” Supervisor Zack Scrivner said at last month’s board meeting. “This notion that if we just stopped producing oil in Kern County we’ll fix global warming, that’s ridiculous, because it’s being pumped out of the ground all over the world and being brought in here on tankers and sitting in ports.”